Tibetan chopstick fonts

In China it seems de rigueur to use Tibetan-looking fontified Chinese characters to make posters and book titles, etc., about things related to Tibet. I’ve always found this practice to be vaguely offensive, perhaps because of the “chopstick” font that you see sometimes on Chinese restaurant menus. (You know, the kind that’s supposed to be vaguely reminiscent of brush strokes in Chinese characters, but if you ever opened your own Chinese restaurant you would only ever use such a font in an ironic sense.)

In China it seems de rigueur to use Tibetan-looking fontified Chinese characters to make posters and book titles, etc., about things related to Tibet. I’ve always found this practice to be vaguely offensive, perhaps because of the “chopstick” font that you see sometimes on Chinese restaurant menus. (You know, the kind that’s supposed to be vaguely reminiscent of brush strokes in Chinese characters, but if you ever opened your own Chinese restaurant you would only ever use such a font in an ironic sense.)

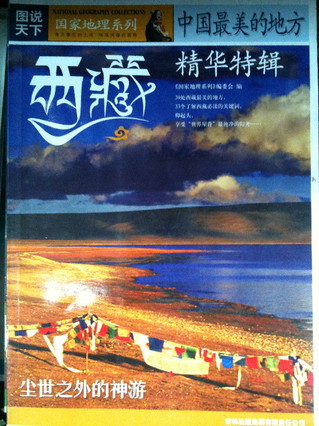

Take, for example, this monstrosity on a book cover (a travel book about Tibet, being sold at a Walmart in Kunming). For those who don’t know Chinese, or can’t recognize the mangled characters, it’s supposed to say 西藏 ‘Tibet’, in that horrible “Tibetan” font. The second character is especially bad: it’s made up of various disembodied bits of Tibetan letters rotated in all sorts of awkward angles. Frankly, it’s butt-ugly, and has none of the aesthetic of actual Tibetan script.

Perhaps why this disturbs me is that you typically never see actual Tibetan script in China unless it’s meant for Tibetans to read. A book about Tibet will talk about all the pretty tourist places you can visit, and how the happy Tibetans just love drinking their butter tea, but will say next to nothing about actually understanding Tibetan history, culture, or language. This book, where the cover uses (badly-done) faux Tibetan script contains zero examples of actual Tibetan script.

I suppose it’s all part of the whole Chinese cultural superiority complex. Remember, you’re only counted as literate in China if you’re literate in the Chinese script. You only “have culture” (有文化) if you’ve been educated—in Chinese. Places have names, but their “real” name is the one written in Chinese characters. Buy a map in China and all the place names in Vietnam will be in Chinese characters (good luck actually using it in Vietnam). The Korean girl who won the Olympics? Her name’s not Kim, it’s Jin.

But hey, if it doesn’t conform to the phonotactic constraints of Mandarin, it’s not real, right?